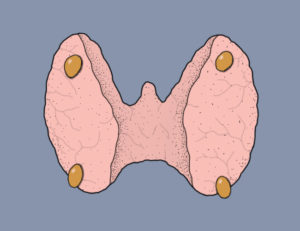

Parathyroid Anatomy

With a few exceptions, the human body has four parathyroid glands. These are very small glands (about the size of a lentil) that sit near the thyroid gland (para = next to). Two of the parathyroid glands are near the right half of the thyroid gland, and two are near the left half of the thyroid gland. However, there is quite a bit of variability in the location of these glands. In rare cases, one of the parathyroid glands may be high in the neck (e.g., near the submandibular salivary glands) or down in the chest (e.g., near the aorta). This variability in location can make parathyroid surgery challenging.

Parathyroid Function

The parathyroid glands serve to control calcium levels in the bloodstream. When calcium levels fall below the normal level, the parathyroid glands produce more parathyroid hormone (PTH). PTH acts to raise the blood calcium level. If calcium levels rise above the normal level, the parathyroid glands decrease production of PTH, thus decreasing the blood calcium level.

Parathyroid Hormone

Parathyroid hormone, or PTH, is a small (84 amino acid) hormone secreted by chief cells in the parathyroid gland. The amount of PTH secreted by the parathyroid glands is controlled by the calcium level in the bloodstream. The higher the calcium level, the less PTH is released. PTH acts by binding PTH receptors located in the bones, kidneys, brain, and pancreas. For the purposes of calcium regulation, the most important of these sites are in the bones and kidneys.

Effects of Parathyroid Hormone

In the bones, binding of PTH to its receptor results in breakdown of the bone matrix and release of stored calcium. In normal individuals, bone is constantly being broken down and rebuilt, with a net zero loss of calcium. If too much PTH is released by the parathyroid glands, a slow loss of calcium occurs. When increased PTH levels are sustained, as in primary hyperparathyroidism, loss of calcium from the bones may result in osteoporosis.

In the kidneys, binding of PTH to its receptor has two effects. One is retention of calcium in the bloodstream, preventing its loss in the urine. The other effect is conversion of vitamin D from its precursor (25-hydroxy vitamin D) into a more potent form (1,25-dihydroxy vitamin D, or calcitriol). Calcitriol acts in the intestine to promote absorption of calcium from food.

Diseases of the Parathyroid Gland

The most common disease of the parathyroid glands is primary hyperparathyroidism. This is most often caused by a benign tumor that forms in one of the four parathyroid glands and produces excess amounts of PTH. In some cases, primary hyperparathyroidism may be caused by separate tumors occurring in more than one of the parathyroid glands. And, in rare cases, it may be caused by hyperplasia (enlargement) of all four of the parathyroid glands. The exact percentages of single-gland vs. multi-gland disease are difficult to determine and somewhat controversial. However, by far the most common cause is a single benign tumor, also known as an adenoma. The only curative treatment for primary hyperparathyroidism is surgery to remove one or more of the parathyroid glands. In exceedingly rare cases, primary hyperparathyroidism may be caused by cancer of one of the parathyroid glands (parathyroid carcinoma). Parathyroid cancer is also treated with surgery.

Secondary hyperparathyroidism is a normal response of the parathyroid glands to some type of external pressure. This external pressure is most often the elevated phosphorus and decreased calcium levels found in the bloodstream of patients on hemodialysis. The parathyroid glands respond to these abnormal electrolyte levels by producing more PTH and slowly growing larger. Most patients with kidney failure who are on dialysis will have enlarged parathyroid glands and abnormally high PTH levels. In almost all cases, secondary hyperparathyroidism can be medically controlled using a medicine called cinacalcet (Sensipar). In rare cases, surgery is required to remove 3 or 3-1/2 of the enlarged glands, in order to lower the PTH level.

Following kidney transplantation to correct end-stage renal disease, the enlarged parathyroid glands in patients with secondary hyperparathyroidism will typically return to a more normal size, and the PTH level will normalize. However, in some patients, the parathyroid glands remain enlarged, and the PTH level stays elevated. This is often referred to as tertiary hyperparathyroidism. If enough time has passed (~1 year) and the parathyroid glands remain enlarged, surgery may be necessary in order to reduce the amount of parathyroid tissue and thus lower the PTH level.